[Note: Spawktalk a.k.a. Sean Last has written a rebuttal to this article for The Right Stuff. You can check it out here. I have opted not to reply since most of the points have been responded to in the comments section of this post, but I would still recommend reading his response, and I've written a reflection on our exchange here.]

I was going to make my next post a work by my father, but since this took me so long, and since my dad encouraged individuals to "do as they see fit, not as they are expected," I went ahead with this post anyway. This is something I've wanted to talk about for a very, very long time, but did not get a legitimate excuse to do so; so, a fair warning: In this post, I will not thoroughly explain the sources I cite (although I can by request), because this post will already take a long time. Instead, I'll include the in-text links as I usually do and continue with my explanation, unless it really is reliant on me to include details of the links I include.

A commenter on one of my other posts asked me a question in regards to something called

“Lewontin’s Fallacy” in light of my page on the debate between Sam Owl and LaughingMan0X. In all honesty, in my research of anthropology (and in the

nearly a year I’ve spent formally learning the facts), I’ve only ever seen

"Lewontin’s Fallacy" mentioned in online arguments. I will still address it, but

much more extensively than anticipated. This is a very complex subject, so in order to fully understand the nature of

Lewontin’s findings on human genetic variation, I will need to explain the

nature of the argument for racial classification for humans, and show why Lewontin, despite committing a fallacy, was actually correct, and where that takes us in the modern realm of anthropology. First, let’s

identify what “Lewontin’s Fallacy” actually is, respond to it, and then we will get into the much broader topic. I do this only to satisfy the request of the commenter before rambling on in a subject he or she may not be concerned about looking into at the moment.

"Lewontin's Fallacy" was coined by A.W.F. Edwards

in a paper criticizing Richard Lewontin's research in human genetic diversity,

specifically his paper "The Apportionment of Human Diversity" from

1972. In this study, Lewontin used single locus analysis to find the fixation

index score (or FST) for human beings; in other words, to find what degree of

variation there is within human populations and between human populations. He

stated that 15% of variation exists between populations, while 85% exists

within populations. He concluded, based on this, that the proposal that human

races exist is unscientific and meaningless.

|

| A.W.F. Edwards |

The reality is, genetic variation exists at a continuum across geographic regions (meaning there are no discrete genetic

categories). Many anthropologists stop here and say: "if there are no

discrete categories, race cannot usefully be applied to humans." Many

counter that this is a fallacy of the beard, but therein lies the problem

that in human variation, there are no extremities.

"Fallacy of the beard" refers to an analogy about

the status of one's beard. The argument would suggest that because you cannot

assign a differential category between 100 hairs on a beard from 102 hairs, or so on, that

statuses of beard lengths (can be simple as long/short, or can refer to things

like five o' clock shadow) do not exist. The reason this is not the case is

because beard lengths have extremities, such as being completely clean shaven, implying that while nominal in nature, the partitioning of such categories of beard status rely on the 'number of hairs' in a ratio level of measurement, where there is a meaningful zero (lack of any hairs). This cannot be done for human genetic variation.

Furthermore, for those of you who are looking to defend your stance on race using the information in this post, I would be very wary when people use this argument, because it's actually a clever strawman that you may not catch immediately. Here is another example of how the continuum fallacy goes, from the Wikipedia page:

Q: Does one grain of wheat form a heap?

A: No.

Q: If we add one, do two grains of wheat form a heap?

A: No.

[...]

Q: If we add one, do one hundred grains of wheat form a heap?

A: No.

Q: No matter how many grains of wheat we add, we will never have a heap; therefore, heaps don't exist!

That last line is where the argument may slip you up. Anthropologists, by and large, do not take the position that race does not exist, but instead that race is subjectively classified, and relies more on the societal context you find it as opposed to any real biological differences. Race does exist, it's just subjective; therefore, arguing that this is a continuum fallacy is a strawman, and cannot be applied.

Furthermore, for those of you who are looking to defend your stance on race using the information in this post, I would be very wary when people use this argument, because it's actually a clever strawman that you may not catch immediately. Here is another example of how the continuum fallacy goes, from the Wikipedia page:

Q: Does one grain of wheat form a heap?

A: No.

Q: If we add one, do two grains of wheat form a heap?

A: No.

[...]

Q: If we add one, do one hundred grains of wheat form a heap?

A: No.

Q: No matter how many grains of wheat we add, we will never have a heap; therefore, heaps don't exist!

That last line is where the argument may slip you up. Anthropologists, by and large, do not take the position that race does not exist, but instead that race is subjectively classified, and relies more on the societal context you find it as opposed to any real biological differences. Race does exist, it's just subjective; therefore, arguing that this is a continuum fallacy is a strawman, and cannot be applied.

There are some important facts to note here. Although

Lewontin drew his conclusion hastily from his premise (that because humans have

more variation within than between populations, then races don't exist), genetic studies have

upheld his findings for the most part. In fact, Lewontin's premise wasn't inaccurate at all. The

average FST of humans does tend to be between 0.05 and 0.15 (although the Rosenberg study sets it at a smaller number, and the Excoffier/Hamilton study sets it at a larger number, the number I refer to is what is generally accepted and is not up for much debate). His "more

variation within than between" finding continues to be echoed in the field

of anthropology not for the conclusions that he drew, but for the fact that he

did successfully fixate the populations of humans on the index. Lewontin's "fallacy" was not in the fixation index, but the conclusion he drew from it -- that races don't exist. No anthropologist really denies the empirical findings of Lewontin's research, but the debate over the existence of objectively defined human races still continues to this day.

|

| There is variation. Now what? |

between human populations, so what does this mean for race? Are these genetic differences significant or not? For the rest of this post, I will be applying the information I have mentioned above to a larger topic: the extent, the pattern, and the meaning of variation in modern humans, as well as historic attempts to understand this diversity. This will take a long time, so I encourage my readers to be patient and feel free to come to and from this post as frequently as what makes you feel comfortable.

Firstly, in terms of evolutionary time, 60 kya (about 60,000 years) is a very short time. That's the estimate that we generally use for the age of modern humans. Starting 60,000 years ago, anatomically modern humans began to expand and occupy every region of the planet, leading us to where we are today. The world is very ecologically diverse, and so various human populations encountered different ecological and climatic conditions. The extent of how far modern human migration has gone can easily be seen in places such as (let me use the expected example) Toronto. This type of diversity comes primarily from our current period of time.

Attempts to understand human diversity go back thousands of years. Yet, one of the first "scientific" attempts to classify humans according to their physical characteristics was by Carolus Linnaeus, who we now know as the founder of modern taxonomic classification. He invented the binomial classification system of genus/species that we continue to use to this day. Once again, this was an effort that goes back thousands of years. For this reason, it's very instructive to review Linnaeus's early classifications of humans based on their observable characteristics. In 1758, Linnaeus essentially used the following classifications and descriptions for each:

Americanus: reddish, choleric, and erect; hair black, straight, thick; wide nostrils, scanty bearrd; obstinate, merry, free; paints himself with fine red lines; regulated by customs

Asiaticus: sallow, melancholy, stiff; hair black; dark eyes; severe, haughty, avaricious; covered with loose garments; ruled by opinions

Africanus: black, phlegmatic, relaxed; hair black, frizzled; skin silky; nose flat; lips tumid; women without shame, they lactate profusely; crafty, indolent, negligent; anoints himself with grease; governed by caprice

Americanus: reddish, choleric, and erect; hair black, straight, thick; wide nostrils, scanty bearrd; obstinate, merry, free; paints himself with fine red lines; regulated by customs

Asiaticus: sallow, melancholy, stiff; hair black; dark eyes; severe, haughty, avaricious; covered with loose garments; ruled by opinions

Africanus: black, phlegmatic, relaxed; hair black, frizzled; skin silky; nose flat; lips tumid; women without shame, they lactate profusely; crafty, indolent, negligent; anoints himself with grease; governed by caprice

Europeaeus: white, sanguine, muscular; hair long, flowing; eyes blue; gentle, acute, inventive; covers himself with close vestments; governed by laws

|

| Carolus Linnaeus |

Similarly, in 1775, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach submitted his thesis for his M.D. entitled De generis humani varietate nativa (or, On the Natural Variety of Mankind). He is now considered to be the father of physical anthropology, and with good reason. Blumenbach, like Linnaeus, assigned to humans five categories representing their types:

Mongolian (yellow)

American (red)

Caucasian (white)

Malayan (brown)

Ethiopian (black)

In classifying these, Blumenbach used a more biological approach in contrast to Linnaeus. At the same time, Blumenbach rejected the notion of multiple human origins, and also rejected the notion of African inferiority from an anthropological perspective. He also recognized the continuous nature of human variation. This is why we consider him to be the father of physical anthropology: his findings have been the basis for studies in this field of science to this day. However, as I said, the classification of human races still remains in debate.

To understand this debate, we have to ask "what is race?" This can be problematic because the term means different things to different people; for some it has a strict biological meaning, for some a cultural meaning, and for some a combination of the two. Here, we will try to observe it strictly by its biological validity. There comes an issue, however: how can we define race in a narrow biological sense? Do these races exist in humans? Can race usefully explain the biological variation found in humans?

The term "race" was officially coined by Comte de Buffon, a French naturalist, in 1745, but one of the first scientists to use the term "race" in its modern context was the French physician and traveler Francois Bernier in his 1684 publication Nouvelle division de la terre par les différentes espèces ou races qui l'habitent, or New division of Earth by the different species or races which inhabit it. Here we see that he used "species" and "race" as being somewhat synonymous, so how will we define it knowing what we do in the modern realm of anthropology?

|

| AAA and others: thank you for your hard work. |

There are many reasons why the AAA, the AAPA and the HGP came to these conclusions. As we have established, races are, by definition, discrete and unambiguous units of classification which are used to explain variation which is mostly continuous in nature. It's important to note, before continuing, that evolution is very complex, and there are many different factors that can influence that variation. The variation in humans, and any species of animal, can be described with their interplay with evolutionary factors.

Consequently, racial classifications can't explain, in any meaningful way, the variation observed in human populations -- this is why there has never been any true agreement among anthropologists on the number of races, from three to several dozen. Before half of my audience pulls up their mouse and diverts to the comment section, this does not mean I am denying that there is biological variation in humans. As Relethford stated in 2002, "biological variation is real; the order we impose on this variation by using the concept of race is not." We are not all the same, the variation is undeniably there; however, creating descriptive categories for humans fails to explain the complex reality of human variation.

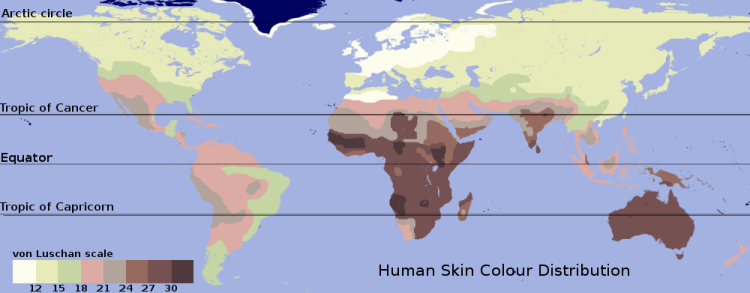

Let me use the example of skin pigmentation. There are simplistic views as alluded to above: red, yellow, white, brown, black. Then there is the more complex, realistic view: there is going to be a huge range of variation in skin tone, and there will inevitably be overlaps between groups. The traits that have traditionally been employed to classify humans in "racial" groups are anthropometric traits (primarily skin color, facial features, shape and size of head and body, underlying skeleton, etc. as shown by the Linnaen classification, for example). However, anthropometric traits are strongly influenced by the environment and are subject to natural selection, which may be acting in different ways for different traits. This being said, natural selection acts in specific genomes, thus different traits often shown remarkably discordant geographical distributions.

Once again, I will divert to skin pigmentation. In the bottom map, the darker regions have darker skin, and the shade gradually becomes lighter as you move north in latitude; in the top map, you see the distribution of the A allele in the ABO blood group. As you can see, the distribution of skin pigmentation is much different from the distribution of the A allele of the ABO blood group. When you think about it, this isn't all that surprising. Remember, there are multiple different factors driving allele frequency change; mutation, gene flow (and isolation by distance), genetic drift, natural selection, etc. To fully understand this, we need a brief overview of how this evolution works.

Once again, I will divert to skin pigmentation. In the bottom map, the darker regions have darker skin, and the shade gradually becomes lighter as you move north in latitude; in the top map, you see the distribution of the A allele in the ABO blood group. As you can see, the distribution of skin pigmentation is much different from the distribution of the A allele of the ABO blood group. When you think about it, this isn't all that surprising. Remember, there are multiple different factors driving allele frequency change; mutation, gene flow (and isolation by distance), genetic drift, natural selection, etc. To fully understand this, we need a brief overview of how this evolution works.Genetic drift and gene flow are evolutionary factors which affect the entire genome. However, at the same time, forces such as natural selection affect only a subset of loci -- in the case of skin pigmentation, the genes involved in the synthesis of melanin. Thus, different traits (and at the genetic level, different loci) can have very different evolutionary histories. So if the concept of race doesn't work usefully for humans, how can we study, in a meaningful way, the biological variation observed in our species?

As detailed, the current study of human variation is an evolutionary one. We try to understand how different evolutionary factors have shaped the diversity of our species. This approach has to be very flexible, since there are many ways to proceed depending on which evolutionary questions we want to answer. Now, we will identify different ways anthropologists study human variation.

Some researchers study human variation at the level of local populations; for example, studies of the social structure and genetics of South American Indians of the rain forest. Other anthropologists study human variation at the level of global major geographic regions; for example, in the most relevant case of Lewontin, studying the patterns of variation within and between major continental groups. We will soon get into the significance of Lewontin's findings, but for now, let us consider two more examples.

Many anthropologists attempt to understand population history using as many traits as possible; for example, studies of gene flow in New World populations. Others are primarily interested in specific traits, trying to understand how evolutionary factors have shaped the variation in those traits in human populations. We have already discussed an example of this: the study of the distribution of skin pigmentation genes and their evolutionary history.

These are examples of the different ways in which anthropologists can study human variation. For decades, anthropologists have tried to answer two important questions related to this topic: what is the extent of variation in human populations, and how is this variation distributed (are there many differences between major geographic groups)? The answers to these questions can be found by studying our DNA.

In spite of the seemingly high variation observed in humans for some anthropometric traits (skin color, shape/size of head/body, etc.), humans show little-to-moderate variation at the genetic level, as alluded to earlier. It is particularly interesting to contrast the genetic diversity observed in humans with that of our closest relatives, the great apes. It turns out that at the DNA level (Y chromosome, mtDNA, and autosomes) humans are much less diverse than the great apes. Consider the chart on the right that I pulled from an anthropology textbook, illustrating the diversity that exists within our populations using Watterson's diversity estimator. It shows that at the genetic level, humans have a diversity level of about 7.5, while chimps lie at 24, gorillas 15, and orangutans 25. Why is there so little variation in humans compared to our hairy relatives?

As briefly mentioned earlier, most molecular anthropologists and human geneticists think that the low diversity observed in humans is due to our recent origin. Anatomically modern humans are a young species, so the level of diversity is relatively low. In addition, there is evidence indicating that humans went through a severe bottleneck in their history -- in other words, the human population was reduced to a few thousand people; however, not everyone agrees about the origins of anatomically modern humans (the very large consensus up until now has supported the Out of Africa hypothesis, but recently the multiregional hypothesis [not to be confused with the candelabra model] has found favor among many anthropologists, including myself; I won't get into this now, I simply wish to identify the two most significant sides of the debate).

But now that we've gone into general perspective of variation of humans, we can get into variation within and between, as promised. We have seen that at the genetic level, humans show less variation than the great apes. There are other important questions regarding human variation, however:

- How is the variation distributed?

- How much variation exists within our populations?

- How much variation exists between, particularly at the continental level?

For this, let's review the evidence at the DNA level and see if we can find an answer.

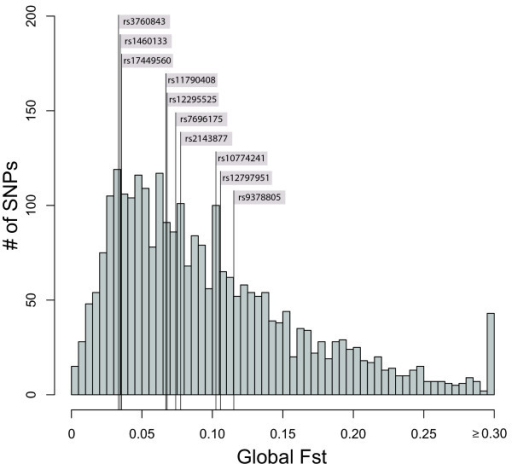

To measure variation within and between populations, the most common statistic is the fixation index, or FST. FST measures the amount of differentiation between groups or populations. An example is the picture shown on the left. It explains the basic mechanisms of calculating the variation between vs. within populations. In humans, there are few genetic markers that have huge genetic differences between populations.

Now, we move on to our guest of honor again. One of the first researchers to estimate the relative degree of genetic variation within and between human populations was Lewontin in 1972. Since his original study, many more have been carried out, using different methodologies and different genetic markers. All of these studies generally show that the percentage of genetic variation between continental groups is only a small percentage of the total variation -- most of the variation is found within populations. As stated earlier, numerous studies indicate that the percentage of genetic variation between continental groups only accounts for about 5% - 15% of the total. Again, this is probably due to the recent origin of our species, plus the effect that gene flow has had in shaping our genetic diversity.

But how do we interpret the results? How can we reconcile the obvious differences we observe in anthropometric traits between human populations with the low values observed at the genetic level? This, apparently, would be a contradiction, but it isn't so. Consider again the factors driving human evolution. Although most traits show very small differences between human populations, some traits can show large differences, particularly those subjected to strong diversifying selection. To help you understand this better, let's clarify some important points.

The estimate of variation between human populations (FST = 0.05 - 0.15) is an average value. The dispersion of FST values around the mean is wide. While the majority of markers show low FST values (FST = <0.15), some markers can have large FST values, and the results of such studies of genetic markers can and will vary. When you can, take a closer look at the FST distribution of

|

| Only 2,750 markers, but you can still see the wide variation. |

Typological racial classifications do not capture the complex pattern of diversity found in human populations. Humans show low genetic diversity in comparison with great apes. Most of the genetic variation found in humans is within populations. In addition to mutation, gene flow, genetic drift and natural selection has also actively shaped our genome, so that for some markers and traits, the differences between populations can be larger than the average (diversifying selection), and for others, the differences may be smaller (stabilizing selection). We are only beginning to understand how these different evolutionary factors have shaped the diversity of our species, but as much as we understand, racial classification is not a useful way to help us to do this; thus, the topic of racial classification, although still much debated, tends to be pushed aside for more useful, productive discussions of explanations for the genetic variation we find in the human species.

In the end, Lewontin may have committed a fallacy by concluding all of this from the premises he had, but he ended up being right regardless.

Thank you for reading.

*For supplementary reading, I recommend looking at the module set by the General Anthropological Division of the American Anthropological Association: http://www.aaanet.org/committees/commissions/aec/gad_module_2.pdf

I would also recommend "Race Reconciled: How Biological Anthropologists View Human Variation."

Follow me on social media!

Twitter: https://twitter.com/AlexisDelanoir

Google+: https://plus.google.com/+AlexisDelanoir0/

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/AlexisDelanoir

Lewontin, R. (1972). The Apportionment of Human Diversity. Evolutionary Biology DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4684-9063-3_14

Rosenberg, NA. (2002). Genetic structure of human populations. Science.